From Drempels to Doors: On Belonging and Inclusion

What inclusion demands of systems, structures and relationships.

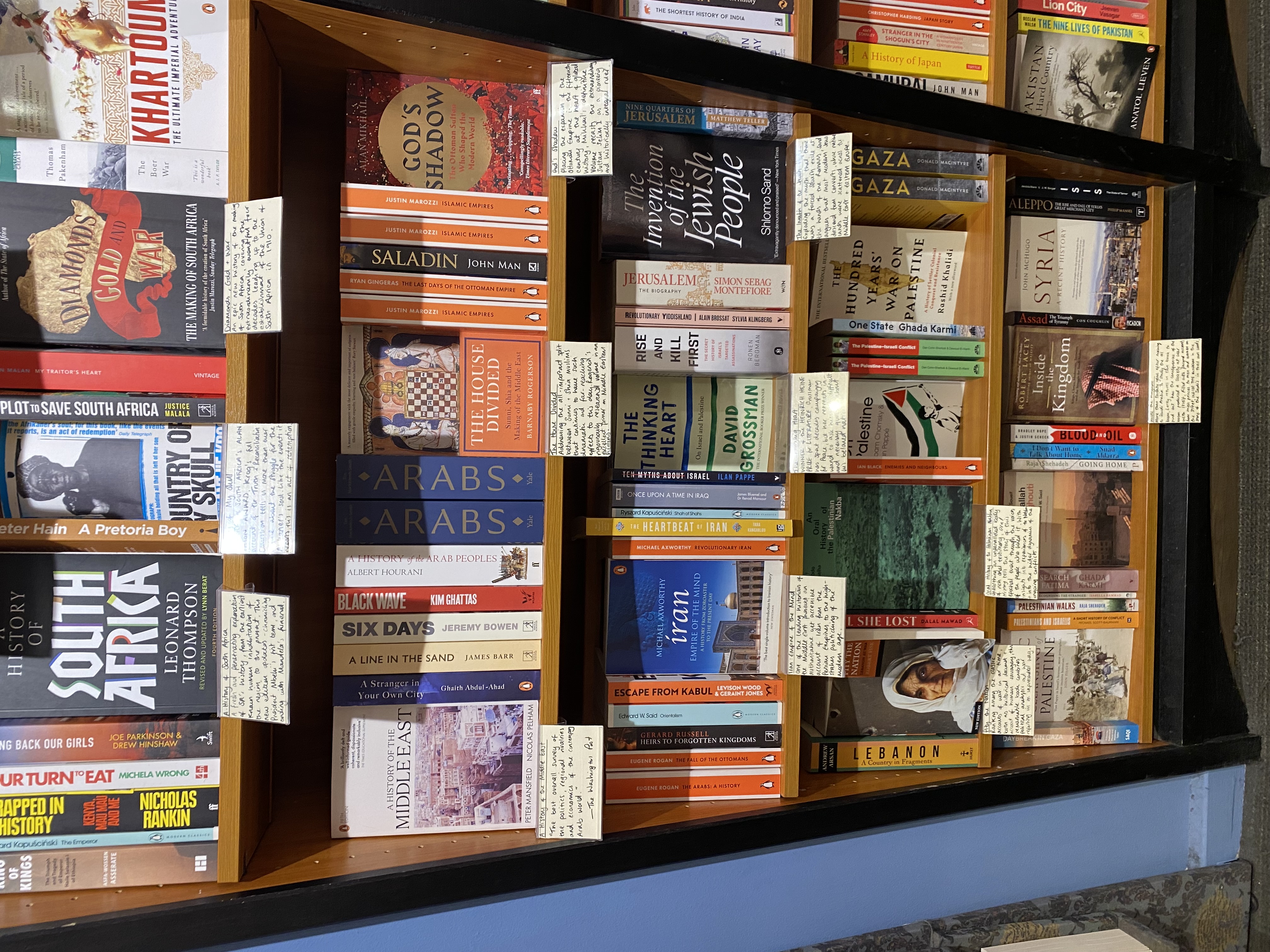

I was a new PhD student in a city where I knew no one. Waterstones in Brussels became my refuge. The smell of paper and ink had always been comforting to me. There, I could sit, read, and be left in peace. No labels. For a while, I belonged.

I was in London for three days, and you can’t be there and ignore Waterstones. On a quick stop, I went straight to the “suggestion of the month” display. It was an old habit, browsing this shelf. By chance, I picked up ‘There Are Rivers in the Sky’ by Elif Shafak. The book was a heartbreaking exploration of the tragedies of the Yazidis and the Aramaic people, and it reminded me that everyone carries a past that isn’t immediately visible.

Before school began, I checked my class lists. I noticed Aramaic names and felt a spark of curiosity.

On the first day, a student arrived late, dropped his backpack, sat, and buried his head in his arms. No interest in English.

During introductions, I started small. I told him I’d read about his people; that in their history, Ashurbanipal built one of the first great libraries. I asked if he spoke and wrote the language. He said he spoke it but didn’t write well; maybe his grandparents could help. I asked if he’d write my name in Aramaic.

Since then, he’s been one of the most active voices in class. In other subjects, his teachers still see resistance. With me, he leans in. The difference wasn’t magic. It was recognition. Sometimes learning begins the moment someone feels seen.

I joined the nascholing “Van drempels naar deuren” by Katholiek Onderwijs Vlaanderen, held in the Flemish Parliament.

William Boeva opened with a question that made the room quiet: “How many of us have a close friend with a disability, not family?” The problem is not only resources; it is distance. Not every sport, lesson, or route fits every body, so we need variants that feel normal, not exceptional.

When Prof. Sara Nijs (KU Leuven) spoke, I noted two lines: “Set the bar high.” “Do not judge before you know.” If we talk about “a school for everyone,” do we mean it? Most of us live with some limitations in different ways. If that is true, who defines “normal”? Why do we ask the many to adapt to a rigid system instead of adapting the system to humans?

I thought of my student with his head on the desk. Respecting his language and culture did not solve everything, but it cracked the door. Inclusion is not chaos; it is intentional welcome with structure.

Sofie Sergeant (HU Utrecht) put it plainly: keep the bar high, make the entrance simple, and say “I do not know yet” early enough that support starts before paperwork.

A panelist extended the point: no young person is a case or a file; they are a world. She followed up with this: when you look at a student, do you see risk or possibility?

We talked about how complex behavior is often diverted to special education, not always from cruelty but from exhaustion and time pressure. The effect is the same: a soft exclusion.

Finally, a crucial distinction: inclusion is not borderlessness. It is responsible hospitality, dignity with boundaries. Structures should serve humans, not the other way around. And a warning: if teachers, psychologists, social workers, and families act separately, support breaks apart. Real inclusion requires alignment.

From a quiet bookshop in 2015 to a Parliament hall in 2025 runs the same idea: spaces make us possible. When a room says, “You belong before you prove anything,” you try. When it says, “Prove it first,” you hide.

I did not fix my student. I fixed my approach and he met me halfway.

You can also read the article here: 👉 What If They Had a Choice?

What inclusion demands of systems, structures and relationships.

Posture, language, and belonging from Görlitz to Brussels

From storks to sessions: why side-by-side fails without design

How to curate, improvise, and land your lessons like a multi-course dining experience

How kindness and clear communication in public service help citizens feel heard and respected

Teaching, Translating, Connecting: A Journey Through European Classrooms and Science Communication

It’s not a problem until it is

Exploring the fraught nature of teaching those who have a choice to not learn.